Author Libuše Hronková

Dance Zone 3- 2091

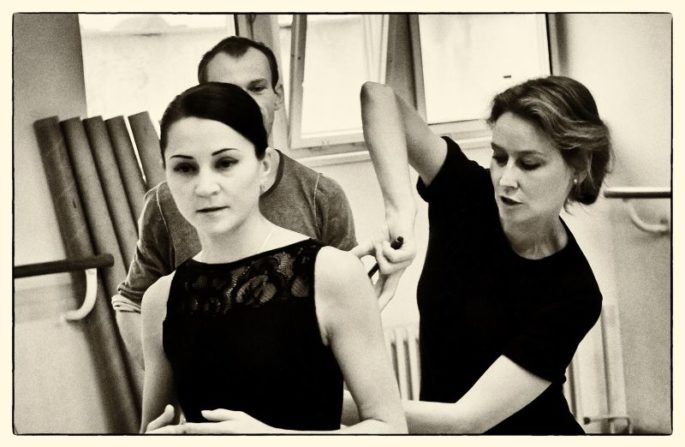

Dancer, choreographer and director Alena Pešková was the head of the ballet company of the F. X. Šalda Theatre in Liberec since 2010. After the 2018/19 season, however, she decided to leave the theatre and become an independent artist again. Where she gets inspiration for her choreographies, how she evaluates her years spent in the Liberec company and what was the reason for her unexpected departure, you can read in the following interview.

After graduating from the Prague Dance Conservatory, you worked for one season at the Karlín Musical Theatre. Why did you leave so early?

I was disappointed with my job in Karlín. I went there because at that time they were thinking of reopening a large ballet company. But that didn't happen and I wasn't very keen on musicals and similar genres. In retrospect, however, any thing that you judge as not very positive at the time turns out to be beneficial. I got musical theatre experience choreographically and dancing-wise.

Then you got an engagement at the J. K. Tyl Theatre in Pilsen, where you danced both classical and modern repertoire.

I'm glad I got to walk through the stone theater. I never had the ideal disposition for classical ballet and was more attracted to contemporary technique. Classical is a staple for me as a choreographer and dancer, but the departures into other styles and techniques were more rewarding for me. I gravitated more towards dramatic, acting and highly emotional roles, although I also danced princesses and fairies. I also had the opportunity to choreograph - my colleagues and I started a group here called Post Festum.

Where do you draw inspiration for your choreography?

From paintings, sculptures, music, but then I have to take the story hostage. But as Jozef Bednárik said: The road to success is lined with the corpses of our best ideas. You want to put your initial idea into the piece at all costs, but then you find that you have to give it up because it doesn't fit into the overall line or rhythm of the production. When I start from a literary draft, I read it several times and rework it into a dance libretto. I have to leave out a couple of side plots and characters and instead visualize what is only talked about on stage in the drama.

You often use original music in your choreography. How do you collaborate with composers?

I try to write them the most detailed musical script possible. Sometimes I'm almost obnoxious and cling to a key, a rhythm or a whole musical form for a dance duet, for example. When I know the plot is strong, I let them have free rein and just write the approximate timing of the duet. But sometimes we miss the mark in our ideas, so I end up using a certain part of the music in a completely different place than it was originally intended for. In those cases, I get inspired by the music in retrospect.

Is it easier for you to have your music written than to choose it yourself from existing songs?

I've said to myself several times that it's much easier to choose from existing music. But I often get to the stage where I want to pick up something that isn't in the piece. Sometimes collages work well, but I find it better to collaborate with another artist. We influence each other - he sends me something and I get new inspiration from it.

The author of the music for your choreographies is very often Gabriela Vermelho. How did this collaboration start?

Ironically, based on a misunderstanding. As a freelance dancer, I wanted to focus more on choreography and started a company Ultra-minimal-ballet, with which I planned to perform the action ballet Jessie and Morgiana. At that time I went to concerts at the Malostranská beseda and Blues Sklepa, where young promising artists such as Petr Wajsar, Honzík Kučera and others performed. Gábina Vermelho sang there with the Epoque Quartet. I really liked it and I thought she was the author of the songs she sang - which she wasn't. I asked her if she would compose the music for Jessie and Morgiana. She agreed, even though I couldn't offer her any decent fee for it. Years later, she confessed to me that she didn't know what she was agreeing to at the time. She'd never composed anything like it. She didn't have the technique to mix the music or the musicians. To keep what she promised me, she recorded all the instruments herself with the help of just a few friends, learned how to mix music, and did it all on the fly. It was nerve wracking because opening night was approaching and the music was nowhere to be found! But in the end she managed everything successfully, and that was the beginning of our long-lasting collaboration. I have to admit that her music inspires me a lot. And there are themes where I hear her music in advance.

What makes you mix different dance styles and theatre genres together?

Maybe it's my overall view of the world. I'm not an advocate of illusionary theater. People should know that what happens on stage, like what happens in life, is not real, that it's just a play. We write it ourselves and we have a chance to influence it. I think the feeling of alienation in life are the cracks through which we can glimpse the true reality.

Your choreographies often include singing and spoken word. Do you feel that the verbal component is necessary to express the plot?

I use the word as a symbol. I don't think the audience would understand the meaning of the work without it. The visual component, the sounds or the film could work the same way. Some viewers need to understand every gesture. I'm at the stage now where I don't need to understand choreography with my head, but with my heart. I wish people who look at my stuff didn't want to know every subtext. A dancer and a choreographer has to know it, has to know why they do each gesture. I cling to that because he's not conveying specific information, but the meaning of it. After watching a well-constructed ballet, the viewer is sure to be enriched at least with emotion if they know little or nothing about the plot.

What choreographies have recently appealed to you as a viewer?

Now I like to look at choreographies that come from the primal base of dance, where the dancers go into a complete trance and don't think. But as a choreographer, I haven't gotten there yet, or rather, it's not my way at all. It's not that I need a plot, but I need a climax, a concrete nameable emotion connected to the music and to the body.

As head and choreographer of the ballet company of the F. X. How did the company change under your influence?

The company now looked consolidated with the last premiere and all types of dancers were represented. The dancers were confident and average or above average in their field - technically and in acting or musically. Most of them worked with the guest choreographer in a very professional way and were able to offer different takes on their role. There is a creative atmosphere in the company. The dancer Marika Hanouskova has grown into a choreographer and the new head of the company.

Is there a great interest in engagement in the Liberec ensemble?

On the part of foreigners, yes. I received a lot of applications from all over the world for this year's audition. We ended up inviting 80 people. Quality Czech dancers usually want to go to the National Theatre, abroad, or do musicals. A few of them came to our audition, but their quality and discipline was far from the foreign applicants. My priority was not to create an international ensemble, it was a virtue out of necessity. When you replace one dancer in a small company of fourteen people, it's the same as replacing twenty in a large company. I needed the audition to last a week so I could see how the person worked and how they fit into the company. Notwithstanding my departure, there should be more new people starting in the 2019/20 season. Overall, the ensemble needed renewal. Those who had been there for many years already had other priorities. I used to release a lot of dancers for various dance activities with the condition that it must not restrict the company's operations. I was glad that they would gain new experience, which they would then share with the other members. Lately, however, their absence from rehearsals could no longer be tolerated.

What keeps dancers engaged in such a small company?

They are attracted to our adventurous repertoire and know a lot about it. International dancers have told me during motivational interviews that in their countries there are companies focused on either pure classical or ultra-independent modern. Nothing in between exists. Every year I tried to give an opportunity to a choreographer from the company to give his own premiere in Liberec. That's also a big attraction. The dancers have always had a quality teacher and repetiteur. I'm a bit sorry that I never got a permanent male teacher. Filip Veverka and Petr Münch were there only occasionally.

In what direction did you try to lead the repertoire of the Liberec Ballet?

When I took up the post I said straight away that I would not perform the great classical ballets because I think that with fourteen dancers of different types they cannot be staged with honour. I wouldn't sign up for that. Fans of traditional ballets can go to the National Theatre to see pure classics. It's not far and it's better than spoiling the taste of adults and children. We did perform The Nutcracker, but I brought the whole thing into the present day. I've cut the classic pas de deux so that the average girl thinks she's a ballerina. Otherwise, I tried for a balanced repertoire - something dramatic for the connoisseurs who have been interested in ballet for a long time, something light-hearted for families, and finally choreographic studios. The big advantage was that no one had much say in the dramaturgy.

But too much dramaturgical freedom can sometimes be tricky.

Every regional theatre should have a chief dramaturge who stands over all the components and coordinates them. He or she will suggest and see to it that, for example, one children's show will premiere this year as an opera, next year as a drama, etc. It happened to us that we almost premiered the ballet Gazda's Robe and the opera Eva in the same season. At the last minute, we decided to move the premieres back one season. When the two productions were performed simultaneously, we told the audience that we were offering a comparison.

Audiences don't complain about the lack of classics in the repertoire?

Nothing of the sort was said in the post-premiere debates. Even if we had borrowed students from the conservatory, as Lukáš Slavický did in České Budějovice, the theatre would not have paid for such a large choir. In the past years, we have presented an educational programme Obsession with Ballet, where the audience could see famous passages from the ballets Swan Lake, Pharaoh's Daughter and others.

With such a small number of dancers, is it possible to effectively coordinate work on one's own repertoire with performing in opera productions?

If we were able to respect the fermans that were assembled in time, the work could be coordinated without any problems. One of the things that caused me to leave Liberec was poor communication with the management of the opera. We make the fermanas for the ballet company fourteen days in advance because our teachers teach at the Prague Conservatory. When we finally put it together and called all the people, the director of the opera came a week later and dictated when he had to have the ballet available. We called everyone again and adjusted the ferman to his requirements. The next day this director came again and again everything was different.

I also lost my nerve when the theatre management repeatedly explained that each company has its own specifics and that the ballet cannot sit on a bus on a tour with the opera a week before the premiere. They told me to rehearse the choreography ahead of time. That's like telling an athlete to run 500 meters a year in advance and then somehow run it at the Olympics. I hope things get better now. Marika Hanouskova has a good relationship with the head of the opera.

What is the pedagogical and rehearsal background of the ballet company?

Mária Gornalova works half-time as a soloist and half-time as a teacher. She trains and rehearses opera repertoire. Other teachers and rehearsers in the 2018/2019 season were freelancers. There is no ballet hall in the Šaldov Theatre. A week before the premiere, there are rehearsals on stage, but the lighting technicians need to prepare the lighting at the same time. Everyone is doing their job, but no one can concentrate properly. Lately, I've been standing helplessly on stage, not knowing who to yell at - the lighting people to stop yelling at each other so the dancers can focus on their training, or the teacher to speak softly so the lighting people can understand each other better. Ballet doesn't have its own technicians or dressers. We borrow them from drama or opera. When the opera technician goes on tour, we can't perform because there's no one to put on the show. Then you find that after the premiere you don't play the show for maybe a quarter of a year and for operational reasons you don't have a chance to try it on stage again. You have to fight with such operational problems all the time in Liberec. On the other hand, the theatre will tell you that the opera doesn't have a permanent soloist. Nowadays, many opera soloists are touring to different theatres and the whole running of the theatre is subject to their time availability.

So ballet does not have an equal status among the companies.

He's pretending that we do, but we're very limited by the fact that we don't have our own equipment and chaperones. The drama and opera companies are also larger.

How does the audience receive your choreography?

During discussions with the club of friends of the Liberec Opera and Ballet, I was surprised that some of the older ladies were much more perceptive than many critics. I have never pushed ultra-modernism into the theatre that they didn't understand. Still, at first people told me that they would rather see choreographies to classical music by Dvořák, Smetana and others. I replied that such an approach belonged to the past and that we needed to move in that direction. Surprisingly, they came to see the performance again and then acknowledged that I was right. I had a lot of respect for the new audience - teenagers who thought ballet was three hours of boredom. In the end, they were pleasantly surprised and very receptive at the talks. The simultaneous combination of gesture and music can sometimes say more than words.

Weren't you afraid that your choreographies would become stale?

I tried to approach each piece differently so that I could always look forward to something new. But then I got to the stage with the Liberec ensemble that I had nothing to surprise myself with. Until then I was convinced that I was doing everything a little differently. The penultimate production of Creation was completely different.

Would you ever like to try choreographing for a large ballet company?

I have never choreographed for an eighty-member ensemble before and working with such a small ensemble as the one from Liberec cannot inspire indefinitely. I can feel it now. In big theatres you can choose your interpretation. People behave differently if they have competition. For some it's adrenaline, for others it's death. But not every dancer has the character to develop when there's someone more incisive next to them. Each company has its own specifics that the choreographer has to deal with. Doing a big ballet for 14 people is always a challenge.

In what sense?

The important thing is what you want to say and then play the game with the cards you get in your hand. Sometimes the resources you get are very limiting. I've probably said this a few times in other interviews, but I'm fascinated by the biography of Igor Stravinsky. He quickly understood that an artist can't have absolute freedom or it's the creative end for him. He had no money or good performers in Russia, and yet he did brilliant things. When he came to Paris to Sergei Diaghilev, he got money and brilliant performers. He knew that was the end of his creative work. He began to consciously limit himself artistically, for example, by what notes he was allowed to use in his new composition. That's incredibly brilliant. If someone had told me that I had great performers and a lot of time and money and I had to create something brilliant, I would probably have felt a lot of pressure.

Why did you decide to leave Liberec after nine years?

I couldn't secure better salaries, quality facilities for the dancers and, on top of that, the choreographic studios were in danger of being closed down. I tried to get the dancers who had been dancing solos for two years at least into the twelfth grade. The director compensated their lower grade with bonuses, which is nice, but for me it was more a question of honor and respect for our craft. For a long time I have been asking for a cushioned floor in the hall. The dancers are destroying their knees every time they jump because there is concrete under the ballet floor. Under these conditions, I could no longer guarantee that I could keep a quality company in Liberec. I don't want to sign my name to something of lesser quality than what was there before. And finally, I had exhausted myself as an artist because playing the same cards over and over again was no longer fun or challenging for me. I need a change as an artist and as a person. I was already feeling the wear and tear on each other, I couldn't give them the same enthusiasm as before.

What are your plans for the future?

I'd like to stay freelance. I'll be happy if I can do that. I'm almost full for the 2019/20 season. I also have quite a few topics in my drawer, and if any more offers come in, I'll be happy. I'm feeling drained by organizational work and need to soak up some time right now. I want to catch up on all the things I didn't have much time for as a boss: learning new styles in dance, reading literature, going to shows... And maybe I'll revive Ultra-minimal-ballet.

Alena Pešková

In 1994 she graduated from the Dance Conservatory in Prague. After one season at the Musical Theatre in Karlín, she worked at the J. K. Tyl Theatre in Pilsen. Since 1999 she has worked as an independent dancer, choreographer and director. She has toured Europe, Japan and South America. As a choreographer, dancer and director she has collaborated with the J. K. Tyl Theatre in Pilsen, the State Opera Prague, the Czech Chamber Philharmonic, the North Bohemian Opera and Ballet Theatre, the Vienna Walzer Orchestra, the Manuel Theatre, etc. She has choreographed for operas, musicals, festivals, openings and commercials. With her own libretti, she has created full-length ballets such as Marysha, Café Aussig, Periferie, Jessie and Morgiana, The Nutcracker, Blood Wedding, Gustav Klimt, Cinderella, A Midsummer Night's Dream, A Midsummer Night's Dream, The Rite of Spring, Romeo and Juliet, Creation, The Taming of the Shrew, The Tempest, etc. She directed the operas Carmen, The Magic Flute, Il Trovatore, etc. She is the founder of an independent association of professional dancers called Ultra-minimal-ballet (UMB), which had its debut in 2008 at the Blues Sklep with the choreographies 5 m2 to the music of P. Wajsar and Jessie and Morgiana to the music of G. Vermelho. From September 2010 to June 2019, she served as choreographer and ballet director of the F. X. Šalda in Liberec.

She has twice been nominated for the Thalia Award. Among her most notable roles are Marguerite (The Lady with the Camellias), Lisetta (Vain Caution), Rebecca (Carmina Burana), Morgiana (Jessie and Morgiana), Titania (A Midsummer Night's Dream), Pamina (The Magic Flute).

Comments are closed.